Owen and Doris Williams

In 1917, just before the outbreak of the First World War, 14 year old Owen Williams came to Stanmer to work for the 6th Earl of Chichester, Jocelyn Brudenell Pelham.

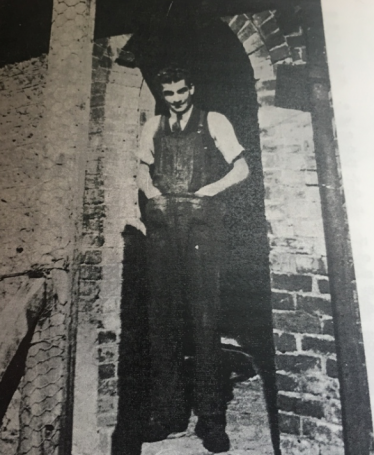

Owen worked on the Stanmer Estate for the next 20 years, from a miserable start downstairs at the Mansion, to the carpenter’s shop in the Estate yard. In this first photo, Owen is standing in the doorway of his workshop, the bothy next to the old cart lodge at the entrance to the Walled Garden. Incidentally, both buildings remain, opposite the Palm House, and have undergone recent improvements.

Owen’s wife, Doris, wrote a vivid account of his life in her book Turn Back the Years, which is not only bursting with richly detailed stories of life below stairs on a country estate in Edwardian times, but offers a unique source of local and cultural history from 100 years ago, as mechanisation transformed the Downland estates and tractors replaced traditional oxen and horses.

But back in 1937, dramatic events were about to impact on the direction of Owen’s life, when the deeply talented Estate Carpenter, Francis Jude Jones, took his own life in the woods behind the old Rectory, the home he shared with his unmarried sister Lily (Elizabeth).

Here is Owen’s own account from p163:

Arriving at Stanmer one morning to start my working day, fully expecting it to be much the same as any other. I was busy in the carpenter’s shop, when a person from the village came in to give me a verbal message from Miss Jones. What I was told sent me hurrying to Miss Jones’s house immediately.

She had sent word of her extreme concern for Frank, as he was nowhere to be found, in the house, or garden. She had been searching for him for some time. More serious he had left a note on the table, which she gave me to read.

On reading the sad suicide note Frank had left for his sister, Owen organised a search party who discovered Frank’s body in the woods behind his garden, along with the shotgun he had used.

I was asked to take over Frank’s duties as Estate Foreman literally within hours of Frank’s death. Mr Anderson giving me no time to consider the matter, saying I was quite capable of doing the job. I had after all been employed nearly twenty years as a carpenter, certainly well aware of what the duties of an Estate Foreman involved.

The question now arose, as to whether I should move to Stanmer to live in the Foreman’s house. I was still a bachelor, living in Brighton with my Mother and elder brother. The prospect of living in that gloomy old house did not appeal to any of us. We decided to remain in the town, so the Old Rectory stayed vacant, never to be lived in permanently again.

Such a tragic day for the Jones family, and for the local community, with the loss of such a highly skilled resident craftsman. Lily moved to East Hoathly, to her uncle’s family, the ‘gloomy’ old house remained unoccupied until billeted French Canadian soldiers ‘reduced it to ashes‘ in October 1940. They had built huge fires in the grates, piling logs high then leaving them unattended. In one of the bedroom grates upstairs, a blazing log rolled unobserved onto the wooden floorboards and it was not long before the whole house was burning fiercely.

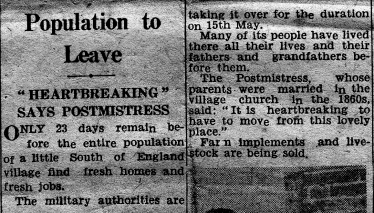

As the (unidentified) newspaper clipping shows, the gentle pace and peaceful life at Stanmer came to an abrupt end two years later. Here’s Owen again (p175), having just handed over a collapsible crucifix he had made to be carried into action:

The Padre departed and I never saw or heard from him again; so never learned if he survived the war. The crucifix he took into battle was one of the last things I made in the workshop, before the blow fell. When homes, jobs and security vanished almost overnight.

In April 1942, a stunned village learned, the whole of Stanmer Parish had been commandeered by the War Office, as a battle training area for the troops.

Residents had lived for a year already surrounded by troops and equipment, but this was different. The War Department now wanted exclusive use of the area, including the village and farms, to prepare for the invasion of Europe.

We were given fourteen days to pack up all our belongings, find other jobs and homes, elsewhere.

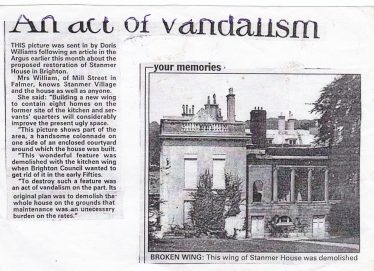

This pattern was repeated across much of the South Downs with many medieval settlements, farms and buildings becoming targets for tank and artillery training. Many were lost for ever, but Stanmer benefitted from a generous post-war compensation package from the French Canadian government, funding the total renovation of the damaged village, so skilfully accomplished that it’s hard to see where the old met the new. Regrettably, the Rectory slipped through the net and was demolished.

When Owen Williams retired in 1977, he was awarded an Honorary M.A. in recognition of services rendered to the University of Sussex, since becoming their first employee in 1961. Sadly Owen did not live long enough to see his story in print, he died on his 85th birthday, 15 October 1988, two years before the book was published.

Doris Williams also wrote about life in nearby Falmer, where she lived in Mill Street: Falmer Parish Reflections, was published in 1985 by the University of Sussex, where Doris and Owen had both worked and met (again), and is still available and also well worth a read.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page